by Rory O'Hanrahan

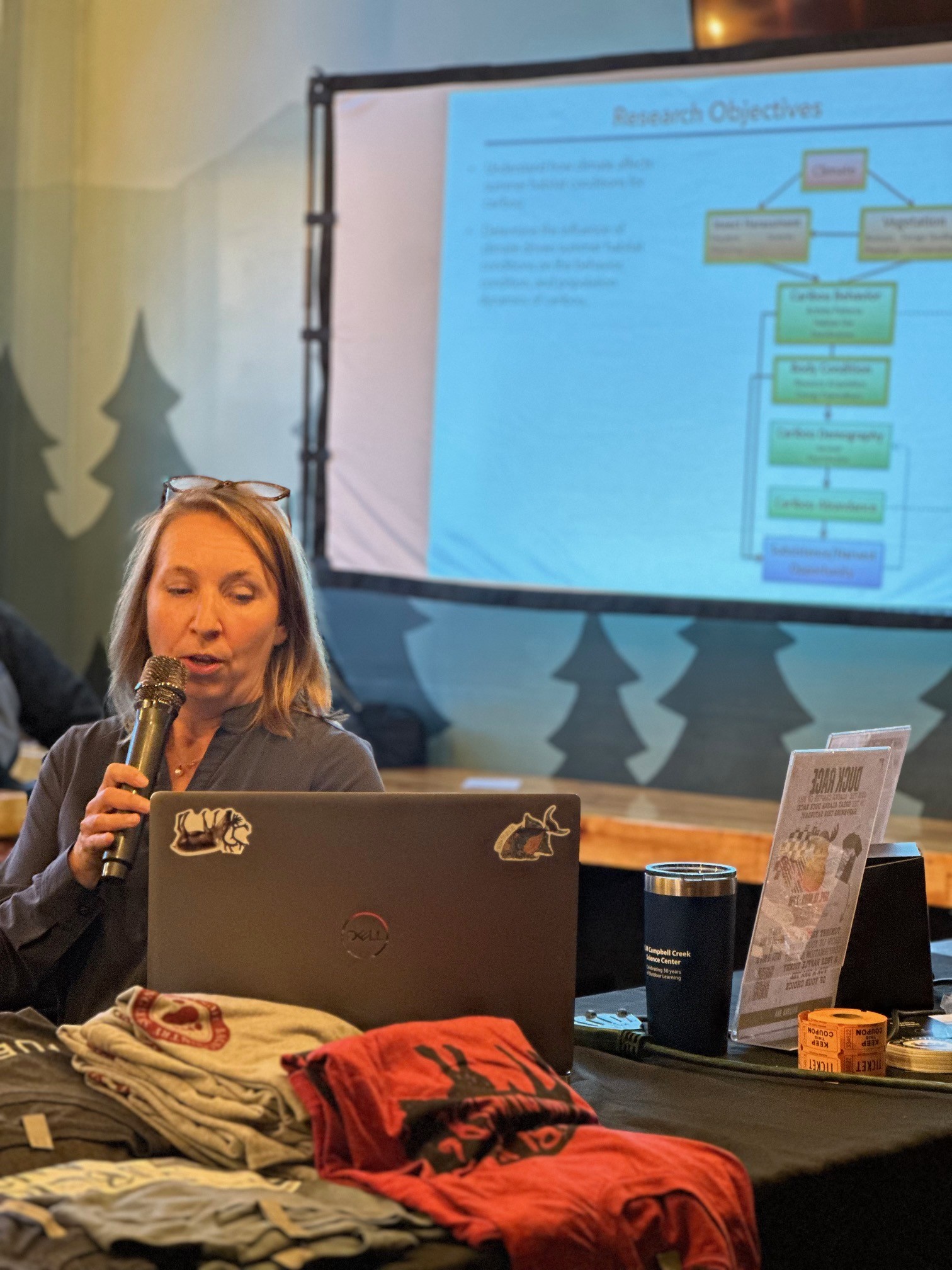

In early September, Backcountry Hunters & Anglers hosted Dr. Heather Johnson at Double Shovel Cider Company to discuss the changing arctic landscape and the Western Arctic caribou herd. Dr. Johnson is a research wildlife biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Anchorage. Her work focuses on large-mammal ecology, especially Alaska’s migratory caribou. Using GPS satellite collars, collar-mounted video, body-condition measurements, and habitat analyses, Dr. Johnson’s team studies how environmental changes affect caribou survival, movement, and reproduction.

During her talk at Double Shovel, Dr. Johnson outlined the major scientific findings influencing the status and future of the Western Arctic caribou herd, one of the largest and most culturally, ecologically, and subsistence-important herds in North America.

The herd, once over 450,000 animals in the early 2000s, has declined substantially in recent decades. Recent surveys indicate the population remains far below historic highs, with continued variability driven by nutrition, weather, predation, and harvest pressure. Dr. Johnson emphasized that declines of this magnitude are not unprecedented, but they require careful, coordinated monitoring and management.

Caribou survival and pregnancy rates depend heavily on summer forage quality. Warm summers with high insect harassment reduce feeding time, lower body condition, and can depress calf production. Dr. Johnson’s team links satellite based plant “green up” data with collar mounted video to quantify how much time caribou lose to insects and heat.

Caribou track newly emerging vegetation across enormous landscapes. Earlier or more variable spring green up can cause herds to shift summer ranges, altering everything from migration pathways to exposure to predators and human activity. The Western Arctic herd has shown substantial year-to-year movement changes associated with shifting plant phenology.

Photo: Rory O'Hanrahan

Caribou tend to avoid infrastructure such as roads or energy sites, even when the physical footprint is small. This avoidance effectively increases habitat loss and can alter migration routes or access to key feeding areas. Dr. Johnson stressed that the “indirect” effects of development often exceed the direct footprint.

GPS collars with built in video revealed when and where insects are worst, exactly which plants caribou are feeding on, and time budgets (feeding, resting, moving) that connect the environment to population trends. Dr. Johnson showed videos to attendees demonstrating different feed types and examples of insect harassment. These tools help managers understand why the herd is changing, not just that it is.

Photo: Heather Johnson

Caribou management must account for more unpredictable weather and seasonal patterns. Reduced body condition years can create multi-year echoes in population numbers, affecting both subsistence harvest and sport opportunity. Protecting migration corridors, minimizing disturbance in key seasonal habitats, and maintaining flexible harvest strategies are essential. Dr. Johnson reinforced that collaboration between agencies, tribes, local communities, and conservation groups, like BHA, is crucial for sustaining the herd for future generations.

Photo: Rory O'Hanrahan

The Western Arctic caribou herd is facing interacting pressures from climate, nutrition, insects, human disturbance, and long-term population cycles. Dr. Johnson’s research helps reveal not only where caribou go, but why they make the choices they do. Understanding these mechanisms is the foundation for informed conservation. BHA hopes to help ensure Alaska’s caribou remain abundant, wild, and accessible to the people who rely on them.

335